1st Workshop on Inter-networking challenges for AI, collocated with CoNEXT'25

December 1, 2025

HKUST, Hong Kong,

China

Report on 1st workshop on Inter-networking challenges for AI

- Antoine Fressancourt

- Dirk Kutscher

Introduction

The 1st workshop on Inter-networking challenges for AI (INet4AI), collocated with ACM CoNEXt’25, was held on the 1st of December 2025 in Hong-Kong. The workshop was inspired by ongoing discussion in the IRTF on research challenges for (inter-)networking technologies for AI workloads.

This full day workshop explored some of the networking challenges of large-scale distributed AI workloads in environments, characterized by node and network heterogeneity, as well as dynamically changing resource availability and utilization. During this inaugural edition, researchers from both academia (HKUST, ETH Zurich, Politecnico di Milano, University of Napoli, Tsinghua University, TU Munich) and industry (Huawei, AMD, Microsoft, and others) discussed possible solutions to address the challenges raised by Internet-scale distributed AI systems with four workshop paper presentations and three invited talks. In this report, we will first give a summary of the workshop papers and invited talks. Then we will draw some general remarks regarding the ongoing efforts done in our community to address INet4AI challenges.

Workshop Papers

The workshop featured 4 paper presentation, addressing both the use of AI to tackle large scale networking challenges and network optimizations (AI4Net) and the adaptations to better serve AI workloads in a heterogeneous environment distributed at a large scale (Net4AI).

AI4Net paper 1: Self-supervised Application-level Network Traffic Inversion

Shaked Leibzirer, research scientist at Huawei’s Tel-Aviv research center, presented the work done in his laboratory on the fine-grained monitoring of network traffic. Such a monitoring is essential for large scale network operators (service providers, large campus networks, etc). However, due to resource limitations, traffic data is often collected using packet sampling techniques, which obstruct accurate temporal analysis. Although statistical scaling methods can estimate approximate total traffic volumes, they typically fail to capture fine-grained temporal dynamics.

The paper presents a hybrid reconstruction framework is proposed, incorporating statistical modeling and attention-based deep neural network (DNN), which allows recovery of high-resolution application-level traffic from sampled data. The training of the model used in the framework does not require pre-labelled training data. Besides, after the model has been trained, the inference can be executed on CPUs, with adjustable precision, making the method adaptable to lower resources environments. The presentation showed an evaluation of the proposed method on real-world campus network traces. The presented results demonstrate that this method outperforms traditional smoothing and interpolation techniques, enabling precise estimation of application-specific traffic patterns. The framework can be generalized to a range of network monitoring methods to invert network traffic generated by a variety of applications.

During the Q&A, Shaked Leibitzer gave some precisions on the method he presented. First, he mentioned that in the inversion operations, he and his team aim at describing the network traffic at the flow granularity, in order to be able to analyze the exchange of data between peers considering the volume and pacing of the traffic. Reaching this granularity allows to analyze problems arising with conferencing applications, in particular related to the impact of packet drops and congestion events on the perceived quality of the call or multimedia exchange. The precision achieved with the inversion method presented allows the analysis of the experienced QoS per user rather than on a more global scale.

Net4AI paper 1: Latency-Optimal Load Balancing For Distributed MoE Inference

German Sviridov, Staff Researcher at AMD in Singapore, presented a latency-optimal load balancing technique suited for distributed MoE inference. Indeed, expert parallelism (EP) has emerged as a promising approach for scaling mixture-of-experts (MoE) inference across multiple devices. However, EP introduces imbalanced workloads among devices, resulting in poor performance and suboptimal hardware utilization rates.

Prior work addressed this issue by either employing auxiliary loss functions during training to encourage balanced token distribution or by dynamically replicating or reallocating experts across devices during inference. The latter approach can easily adapt to varying workloads, but leads to high data movement overheads that can impact end-to-end latencies and throughput.

In this work the issue of high data movement overheads is addressed by proposing a novel latency-optimal algorithm for expert replication and reallocation. This latency-optimal load balancing algorithm jointly minimizes the load imbalance and the total overhead incurred during this phase. The design of this algorithm has been done in two steps. First, the problem has been formalized as an integer linear programming (ILP) problem, and has been solved to assess the potential gains that could be achieved. Given the long time it takes to solve the ILP, a lightweight heuristic algorithm capable of solving the problem in polynomial time has been devised. Experiments presented demonstrate a reduction of up to 12.5% in MoE execution latency over naive expert assignment and enables us to load balance 2× more frequently compared to existing approaches in the literature.

During the Q&A, German Sviridov clarified that the presented load balancing method was designed to be used in a scale-up network rather than in a distributed scale-out environment, and that latency was the metric that was optimized n this work rather than throughput or efficiency because it is targeted to be used during inference. Yet, it has been mentioned that the proposed algorithm could be adapted to a heterogeneous environment by introducing a normalization step in the algorithm.

Net4AI paper 2: SCALE-CCL: A Scalable Collective Communication Library for Wide-Area Distributed Training

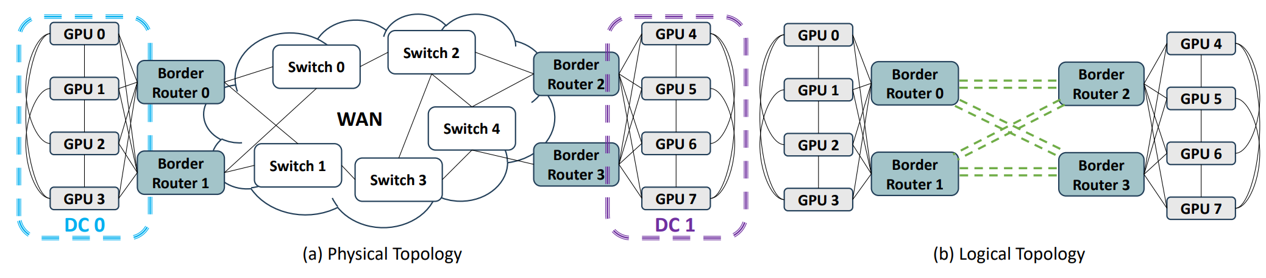

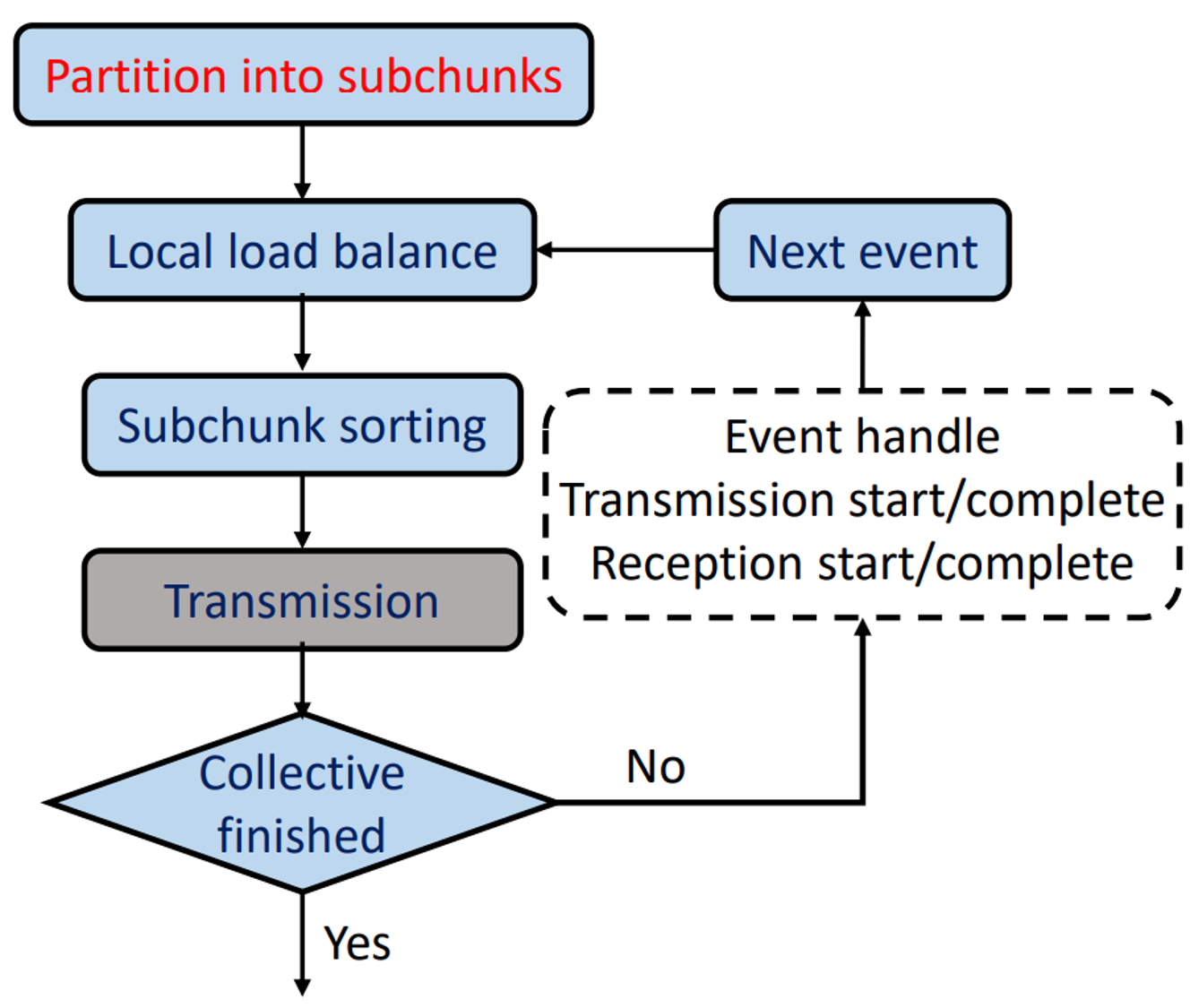

In this presentation, Jiaheng Xiong, first-year Ph.D. student at Politecnico di Milano, introduced the audience to Scale-CCL, a scalable Collective Communication Library for wide-area distributed training.

Scale-CCL aims at being used in training clusters spanning multiple datacenters. Indeed, with the increase in size of large language models, training such models require and increasing amount of (processing) power that cannot be provided in a single datacenter easily. While some recent solutions to adapt collective communications library to a distributed WAN context adopt global optimization techniques, such as Integer Linear Programming (ILP, see previous presentation), to improve communication efficiency, these methods assume static topologies and full network visibility. Such assumptions do not stand in WAN environments, which are characterized by link variability, limited observability, and dynamic traffic patterns.

Scale-CCL is a WAN-aware collective communication library that synthesizes AllGather schedules across geo-distributed datacenters. Scale-CCL combines several techniques: subchunking (Data exchanged between nodes is divided in smaller chunks of data that are distributed independently), local queue–based decisions (each node transfers subchunk based on its own state and neighbor’s known holdings), and a lightweight event-driven scheduler. This allows Scale-CCL to react to WAN variability while keeping schedule generation extremely fast. Experiments show that SCALE-CCL maintains near-optimal completion time while scaling to large topologies and high subchunk counts, making WAN-aware collective scheduling practical for modern cross-DC training.

During the Q&A, Jiaheng Xiong mentioned that while the evaluation presented about Scale-CCL has been done on two rather simple topologies, a goal was to evaluate it over more realistic WAN topologies such as the American-wide NSF topology or a European-scale inter-datacenter topology. Besides, the major difference between this work and TE-CCL was explained. In the paper, Scale-CCL’s performance is very close to TE-CCL, but Scale-CCL is better suited to a dynamic environment. TE-CCL use static link metrics, and use an ILP resolution to find optimal solution. Scale-CCL is better suited to more dynamic situations.

In conclusion, applicability of ScaleCCL beyond AllGather to adapt to various parallelization schemes was discussed.

Net4AI paper 3: You’ve got a few GPUs, now what?! — Experimenting with a Nano-Cluster for Distributed Training of AI Models

In this talk, Giuseppe Aceto, from the University of Napoli Federico II, presented the experiments done in his laboratory with the use of nanoclusters to train AI models.

This work questions the reliance on large hyperscalers infrastructures and provided model in research on large language models. Such infrastructure is out of reach for academic researchers and institutions with limited computational budgets, and cloud services with GPUs offerings may be unadvisable for privacy or security reasons, or for the difficulty in predicting the total cost. In this talk, Giuseppe Aceto presents investigations about the feasibility and limitations of distributed training of AI models in constrained environments by employing a minimal datacenter setup, composed of only two servers, each with 128 CPU cores, 512 GB of RAM, 2 consumer-grade GPUs, and interconnected via standard 1 Gigabit Ethernet. This work focuses on the scalability and the traffic generated during the training of AI architectures (ResNet-18 and GPT2) of different complexity in terms of the number of parameters and layers, and under various parallelization strategies and batch-size configurations. The experimental results obtained highlight critical bottlenecks in network communication and model synchronization. Indeed, distributed training workloads saturate the 1GbE connection between the two nodes used in the experimental nanocluster, making the communication time explode compared to the computation time. Yet, the experimental results also identified viable configurations that offer acceptable training throughput despite the limited hardware. In particular, results show that in limited hardware setups, pipeline parallelism should be favored as it remains viable for both ResNet and GPT-2 models training.

During the Q&A, the similarity between the experimental setup presented and setups typically used in federated learning was mentioned. the main difference lies in the trust model between the nodes participating in the cluster. Reusing some approaches used in federated learning has been identified as a potential follow-up for this work.

Invited talks

Alongside the workshop papers that we introduced in the previous section, we invited three speakers to present their work. Those presentations are complementary to the workshop papers and are aimed at shedding a different light on the specific challenges of Inter-networking for AI.

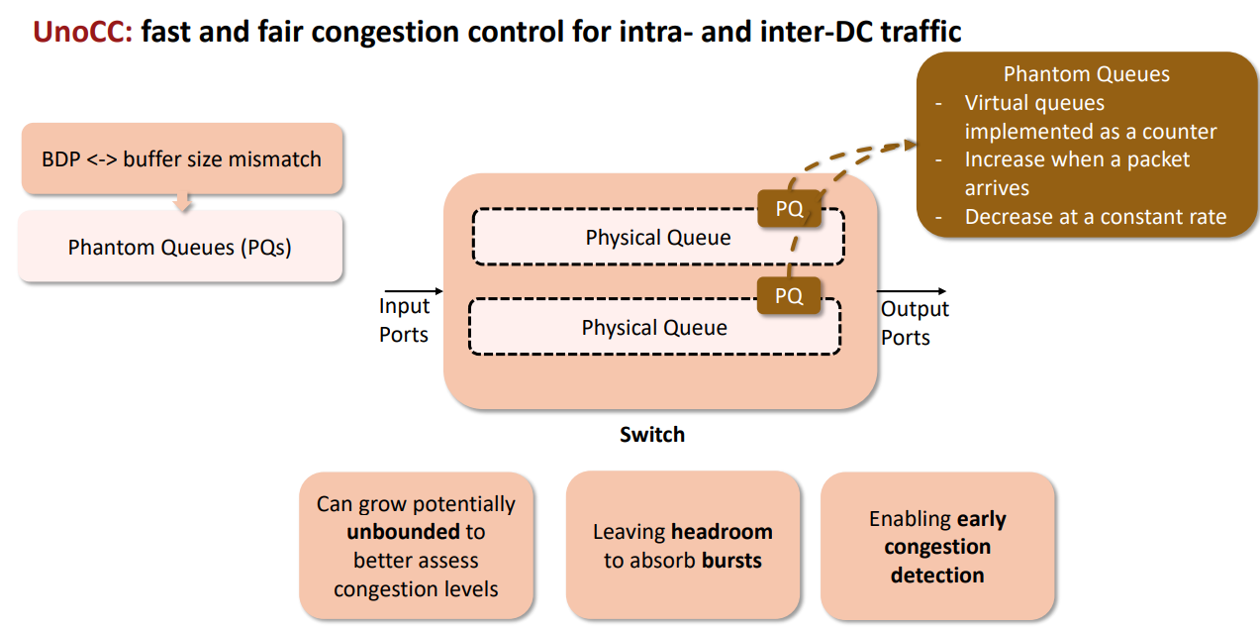

Invited talk 1: Uno: A One-Stop Solution for Inter- and Intra-Datacenter Congestion Control and Reliable Connectivity

In this invited talk, Tommaso Bonato, a PhD student at ETH Zürich and researcher at Microsoft, introduced us to Uno, a solution for inter- and intra-datacenter congestion control and reliable connectivity.

AI workloads, together with cloud computing, is driving unprecedented demand for efficient communication within and across datacenters. However, the coexistence of intra- and inter-datacenter traffic within datacenters, plus the disparity between the RTTs of intra- and inter-datacenter networks, complicates congestion management and traffic routing, as mentioned during the Scale-CCL presentation. Particularly, faster congestion responses of intra-datacenter traffic causes rate unfairness when competing with slower inter-datacenter flows. Additionally, inter-datacenter messages suffer from slow loss recovery and, thus, require reliability. Existing solutions overlook these challenges and handle inter- and intra-datacenter congestion with separate control loops or at different granularities.

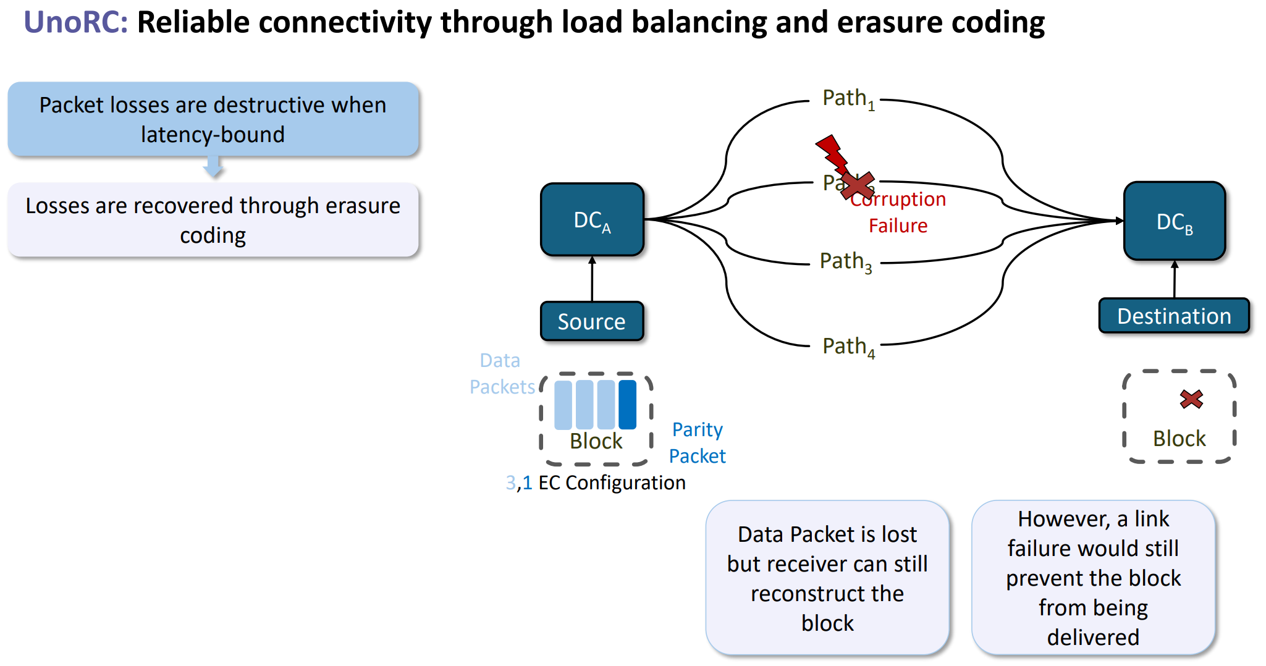

To overcome those challenges, Uno, a unified system for both inter- and intra-datacenter environments, was designed. It is constituted with UnoCC, a transport protocol for rapid congestion reaction and fair rate control, and UnoRC, a load-balancing scheme that combines erasure coding and adaptive routing.

UnoCC combines the use of Explicit Congestion Notification inside a datacenter with phantom queues, i.e. virtual queues with arbitrary sizes that mimic the behavior of physical queues, to match the high Bandwidth-Delay products of the inter-DC connections regardless of the physical queue capacity.

UnoRC, on the other hand, is using erasure coding to recover from packet losses without having to re-transmit packets with a sub-flow load balancing strategy taking advantage of the multiple paths connecting datacenters together to improve the reliability of the inter-datacenter connections.

Evaluation results in a simulated environment show that Uno significantly improves the completion times of both inter- and intra-datacenter flows compared to state-of-the-art methods such as Gemini.

During the questions and answers, Tommaso gave some precisions about the use of Phantom Queues. Those queues are used to decide whether a packet is ECN-marked not at the switch. Then the sender uses ECN marks (through ACKs) to reduce its sending rate/cwnd. So, in Uno, Tommaso and his colleagues tried two assumptions: using “simple” switches with ECN support everywhere, including border switches, or using proper border switches without ECN support. In the latter they restored to latency measurements. Then, Tommaso answered a question about the need for extra buffering at the egress/ingress of the DC. From Uno’s evaluation results, things seem to work okay even without the extra buffering capacity at the border switches, however in practice this is probably not easily doable currently as most border switches have a different design. Phantom queues tend to help more when the buffer is small as one can use them to give more info compared to the real queue.

Invited talk 2: From Homogeneous to Disaggregated Architectures for Large Model Inference

In this invited talk, Mingxing Zhang, tenure-track assistant professor at Tsinghua University and initiator of the open-source KVCache.AI projects Mooncake and KTransformers, introduced his contributions to the development of disaggregated architectures for large model inference.

Traditional large model inference architectures have been predominantly GPU-centric, owing to their significant advantages in both compute power and bandwidth. However, as GPU utilization approaches its bottleneck, achieving further cost reductions requires exploring new optimization paths. Leveraging the distinct advantages of different devices—such as various GPU models or even CPU/DRAM for their bandwidth or capacity-cost benefits—while fully exploiting the model’s inherent properties like sequential dependencies and sparsity, is becoming essential. Designing adaptive computational architectures for this new paradigm has emerged as a critical direction for future co-innovation across algorithms, systems, and hardware. Along the talk, Mingxing Zhang detailed the work he did in Mooncake and KTransformers.

Mooncake is a KVCache-centric disaggregated architecture for LLM serving, used in particular in Kimi. It can be used to disaggregate the prefill and decode phases of LLM inference, and manage to increase the throughput of Kimi’s inference by 75% while trading more storage for less compute. Mingxing Zhang introduced the KVCache Cache system at the center of Mooncake’s serving infrastructure, and highlighted challenges associated with the operation of this cache, as the reuse of KVCache requires deploying PB-level cache that exceeds to size of a single machine, accessible with large bandwidth. Then, Mingxing Zhang presented TENT, a new version of the Mooncake Transfer Engine aiming at tackling the growing challenges raised by the use of heterogeneous interconnects between the systems used in disaggregated inference. TENT integrates three features in that regard: (i) Dynamic Orchestration with an abstraction of the underlying technology serving memory segments; (ii) Adaptive Slice Spraying suited to the latency experienced on each link and (iii) Resilient Self-Healing, mixing both link-Level and transport-level resilience.

KTransformers is a research project focused on efficient inference and fine-tuning of large language models through CPU-GPU heterogeneous computing. KTransformers solves both prefill-specific and decode-specific challenges with a set of novel techniques. To solve the CPU bottleneck experienced during the prefill phase for intense computation, KTransformers facilitates the use of advanced CPU instructions that make computations more efficient. Using Intel Advanced Matrix Extensions, KTransformers includes an AMX Tiling-aware GEMM Kernel, which is nearly 20 times more efficient than classic Llama.cpp prefill operations on CPUs. During the decode phase, KTransformers addresses the latency of CPU/GPU coordination and the lack of overlap between CPU and GPU operations by using CUDA graphs, Numa-aware Tensor Parallelism and Expert Deferral. CUDA graphs capture the full forward operations and remove launch overhead, while carefully avoiding CPU-based operations that introduce breakpoints. Numa-aware tensor parallelism places expert weight slices in the local memory of each NUMA node so that memory access is mostly local, avoiding expensive cross-NUMA memory traffic.

Those technologies are open source, and included in several major open source inference engines.

During the questions and answers, several questions revolved around the efficiency of the KVCache reuse strategy adopted in Mooncake. Mooncake is looking at the work done on Cacheblend, but observes that CacheBlend’s cache stitching strategy shows some problems, and require adaptation and offline recomputations to be more efficient. This is a topic of current works done by Mingxing Zhang’s team.

Invited talk 3: Debriefing the Open Innovation Platform for UnifiedBus

In this talk, Wenjia Wei, technical expert at Huawei, presented us a set of tools allowing researchers to collaborate on the design and development of systems using UnifiedBus.

UnifiedBus (UB) serves as a high-performance interconnect protocol specifically designed for SuperPod networks, unifying IO, memory access, and communication. To empower the academic community to explore innovations in architecture, protocols, and algorithms within this framework, Huawei introduced five open innovation platforms. This talk presents these platforms in detail: the UB Simulation Platform, UB Protocol Verification Platform, Scale-Up Prototype Platform, SuperPod Networking Innovation Platform, and Scale-Out Prototype Platform.

the UB Simulation platform is a network simulator based on NS-3. Its goal is to allow the research community to investigate several topics, such as the design of high-reliability, low-cost, traffic-affinity topologies, the optimization of collective communication operations with UB, novel transaction ordering and reliability mechanisms, transmission control mechanisms or new adaptive routing, LB, CC, and QoS algorithms suited for UB. This tool provides algorithm a bit in advance of the UB specification, and can be used to discuss future requirements and needs of the research community. While this simulator is used to explore new ideas, the UB protocol verification platform is used to make those ideas lad on a correct and verified set of protocol mechanisms. It can be used to verify the correctness of protocol designs and configurations, the compatibility of new designs and the robustness of control plane algorithms.

While the two previous tools were focused on software designs and simulations, the Scale-Up prototype platform, the SuperPod networking innovation platform and the Scale-Out prototype platform are aimed at testing those innovations on actual hardware. Those platforms feature UB-compliant network equipment as well as prototyping hardware platforms on which FPGAs can be programmed to test implementability of new protocol mechanisms.

General remarks

In the workshop papers presented, several assumptions of distributed AI infrastructures serving large language models were questionned in order to distribute such systems over the Internet. All those articles introduce heterogeneity in the management of distributed AI workloads. Indeed, while considering a distributed system as completely homogeneous and fully connected makes load distribution and schedduling easier, this assumption does not hold except for newly built, large clusters connected using scale-up networks. In “Latency-Optimal Load Balancing For Distributed MoE Inference” and “SCALE-CCL: A Scalable Collective Communication Library for Wide-Area Distributed Training”, heterogeneity is embraced during the schedduling phase, complexifying the optimization model used to allocate datachunks, model parameters and requests and requiring those works to adopt heuristics to make allocation and load distribution of inference or training workloads in a short time. Beyond schedduling, the invited speakers also mentionned the need to work on systems and protocol adaptations to address heterogeneity in distributed systems. In Uno, this translates in the design of phantom queues to address congestion issues arising from the difference in bandwidth-Delay products between intra-DC and inter-DC links, while in mooncake a novel transfer engine abstracting both scale-up and scale-out links is being designed and developped. In “You’ve got a few GPUs, now what?! — Experimenting with a Nano-Cluster for Distributed Training of AI Models” embracing heterogeneity comes with a goal to question the perceived necessity to use infrastructure at an hyperscale to work on large language models. In that regard, this work contributes to distributing AI workloads following the initial Internet philosophy to allow every network, large or small to interconnect and exchange data. This intention is also at the heart of several federated learning projects, which tend to couple distribution among heterogeneous and low resource nodes with the retention of control over the data used in training, fine-tuning and inference.